Unlocking the Mystery of a Lincoln Relic

The Chicago Historical Society has on display a lock of hair, allegedly from Abraham Lincoln, among its other Lincoln relics. It is accompanied by an old note that reads—“Taken from President Lincoln’s head after he was shot, cut from the spot where the ball passed through. Washington, D.C., April 26th 1866.” Two names are listed underneath this testimony—“Mrs. M. Laurie” and “Belle C. Youngs.” A crease line in the notepaper crosses the middle initial of Belle Youngs’ name, and, I believe, has caused that letter, which I read as a “C” to be read by the curators as an “A.”

The Society notes that “There is no record of how the relic entered the collection, and the identities of Mrs. Laurie and Belle Youngs are unknown.” The Society has organized a team of investigators to try to solve problems of provenance of its Lincoln relics. It has also set up a website exhibition—Wet with Blood—and has invited information that will help identify the relics. The Society is especially concerned to maintain the physical integrity of the pieces, rather than risk destroying them in collecting DNA material and other kinds of forensic evidence from them.

I can identify the ladies named in the note. Whether this will support or undercut the relic’s authenticity is an open question.

They were indeed intimates of the Lincolns—they were spiritualist mediums at whose home the Lincolns both attended séances, and who were invited to the White House to conduct private sessions. They began their acquaintance with the Lincolns—especially Mary Todd Lincoln—in 1862, not long after the death of the Lincoln’s son Willie. They were Mrs. Margaret Ann Laurie and her daughter Belle.

The Laurie Family

Mrs. Laurie was born in Washington, as Margaret Ann McCutcheon. In 1830, she married another Washington native, Cranstoun (sometimes spelled “Cranston”) H. Laurie, who had been born in 1808. Cranstoun was the son of the Reverend James Laurie, D. D., the founder and first Rector of the F Street Presbyterian Church, which was later called the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church. That church is only a couple of blocks from the White House. During Andrew Jackson’s term of office, Cranstoun Laurie was appointed to a position in the Post Office Department, as Chief Statistician. He remained in that job throughout his career.

The Lauries had three children. Mary Isabella C. Laurie, called “Bell” or “Belle,” was their oldest child. They also had two sons—Lewis F. L. Laurie and James (“Jack”) Craling Laurie—and they adopted a daughter, named Emma. Although Cranstoun’s father was Rector of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church until the early 1850s, the records of the Church do not show Cranstoun or his wife or his children as having been members. They may have attended, however—Abraham Lincoln sometimes went to services at that church, after he moved to Washington to be President. (Reverend Laurie had retired by that time, and its Rector was Phineas D. Gurley.) Lincoln rented a pew there, but never became a member, although his wife Mary did.

In the 1850s, the Cranstoun Laurie family had become devoted spiritualists. The entire family began to exhibit various “mediumistic” abilities. One of these abilities was that of automatic drawing and painting. Emma Hardinge wrote about their “spirit art” in an essay, noting that their “immense maps, or charts, so to speak, of floral luxuriance [. . .] excited the astonishment and admiration of all beholders.” Some of the paintings rendered by the family were of forms—we would today call them abstract or surreal forms—that appeared to reveal unearthly realities.

Hardinge Describes the Lauries’ Spirit-Art

The two strongest mediums in the Laurie family were Margaret and her daughter Isabella. By 1862, Belle had married Lincoln friend and supporter, James J. Miller, but still lived in Washington with her parents and her own two small children. The Lauries’ home became a center of spiritualist activity in Washington, where many people—including high Government officials—went to “investigate” spiritualism. Margaret Laurie’s specialties included contacting spirits of the deceased for messages, and using “magnetic” or spiritual powers for healing. Belle used her gifts to produce physical “phenomena,” especially the levitation of the grand piano in their parlor—and pianos elsewhere.

Mrs. Belle Miller, Mr. Laurie’s daughter, was one of the most powerful physical mediums I ever met. While she played the piano it would rise with apparent ease, and keep perfect time, rising and falling with the music. By placing her hand on the top of the piano it would rise clear from the floor, though I have seen as many as five men seated on it at the time. Mr. and Mrs. Laurie were both fine mediums; and I had met many prominent people during my visits there, who, though not professing to be spiritualists, made no secret of their desire to investigate the subject.—Nettie Colburn Maynard, Was Lincoln a Spiritualist?54-55.

Another young medium, Nettie Colburn, who accompanied the Lauries on a visit to the White House in December 1862, for the purpose of conducting a séance in the Crimson Room (now the Red Room), described the scene as the President came down the stairs:

While all were conversing pleasantly on general subjects, Mrs. Miller (Mr. Laurie’s daughter) seated herself, under control, at the double grand piano at one side of the room, seemingly awaiting some one. Mrs. Lincoln was talking with us in a pleasant strain when suddenly Mrs. Miller’s hands fell upon the keys with a force that betokened a master hand, and the strains of a grand march filled the room. As the measured notes rose and fell we became silent. The heavy end of the piano began rising and falling in perfect time to the music. All at once it ceased, and Mr. Lincoln stood upon the threshold of the room. (He afterwards informed us that the first notes of the music fell upon his ears as he reached the head of the grand staircase to descend, and that he kept step to the music until he reached the doorway).—Nettie Colburn Maynard, Was Lincoln a Spiritualist? 70-71

Lincoln’s former law partner, Joshua Speed, writes a note of introduction to the President for Nettie Colburn and friend Anna Cosby, October 26, 1863. (Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress—Search by Keyword: Enter “Speed” and “Colburn” as text)

Nettie Colburn stayed with the Lauries at their townhouse in Georgetown, where they lived in 1862-63. To that house, the Lincolns came one night for a séance.

One morning, early in February, we received a note from Mrs. Lincoln, saying she desired us to come over to Georgetown and bring some friends for a séance that evening, and wished the “young ladies” [i.e., including Nettie] to be present. In the early part of the evening, before her arrival, my little messenger, or “familiar” spirit, controlled me, and declared that (the “long brave,” as she denominated him) Mr. Lincoln would also be there. As Mrs. Lincoln had made no mention of his coming in her letter, we were surprised at the statement. Mr. Laurie rather questioned its accuracy; as he said it would be hardly advisable for President Lincoln to leave the White House to attend a spiritual séance anywhere; and that he did not consider it “good policy” to do so. However, when the bell rang, Mr. Laurie, in honor of his expected guests, went to the door to receive them in person. His astonishment was great to find Mr. Lincoln standing on the threshold, wrapped in his long cloak; and to hear his cordial “Good evening,” as he put out his hand and entered. Mr. Laurie promptly exclaimed, “Welcome, Mr. Lincoln, to my humble roof; you were expected” (Mr. Laurie was one of the “old-school” gentlemen.”). Mr. Lincoln stopped in the act of removing his cloak, and said, “Expected! Why, it is only five minutes since I knew that I was coming.” He came down from a cabinet meeting as Mrs. Lincoln and her friends were about to enter the carriage, and asked them where they were going. She replied, “To Georgetown; to a circle.” He answered immediately, “Hold on a moment; I will go with you.” “Yes,” said Mrs. Lincoln, “and I was never so surprised in my life.” [. . .] Mr. and Mrs. Laurie, with their daughter, Mrs. Miller, at his request, sang several fine old Scotch airs—among them, one that he declared a favorite, called “Bonnie Doon.” I can see him now, as he sat in the old high-backed rocking-chair; one leg thrown over the arm; leaning back in utter weariness, with his eyes closed, listening to the low, strong, and clear yet plaintive notes, rendered as only the Scotch can sing their native melodies. [. . .] Mrs. Miller played upon the piano (a three-corner grand), and under her influence it “rose and fell,” keeping time to her touch in a perfectly regular manner. Mr. Laurie suggested that, as an added “test” of the invisible power that moved the piano, Mrs. Miller (his daughter) should place her hand on the instrument, standing at arm’s length from it, to show that she was in no wise connected with its movement other than as agent. Mr. Lincoln then placed his hand underneath the piano, at the end nearest Mrs. Miller, who placed her left hand upon his to demonstrate that neither strength nor pressure was used. In this position the piano rose and fell a number of times at her bidding. At Mr. Laurie’s desire the President changed his position to another side, meeting with the same result. The President, with a quaint smile, said, “I think we can hold down that instrument.” Whereupon he climbed upon it, sitting with his legs dangling over the side, as also did Mr. [Daniel E.] Somes, S[imon] P. Kase, and a soldier in the uniform of a major [. . .] from the Army of the Potomac. The piano, notwithstanding this enormous added weight, continued to rise and fall until the sitters were glad “to vacate the premises.” We were convinced that there were no mechanical contrivances to produce the strange result, and Mr. Lincoln expressed himself perfectly satisfied that the motion was caused by some “invisible power” [. . .]

—Nettie Colburn Maynard, Was Lincoln a Spiritualist? 82-91.

Margaret Laurie, apparently “a formidable figure,” became a regular visitor at the White House, to conduct séances, and, as a kind of broker, to arrange spirit circles for others. She appears to have become an intimate and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln during this time—and, according to her, of Mr. Lincoln as well, arranging séances for the Lincolns and some of their friends. Lincoln’s aides, she said, cautioned her about the need to protect the President’s public image, and strongly urged her to secrecy about the meetings, as a matter of State security. Nettie Colburn later wrote that she was also cautioned on the same subject.

Another spiritualist who was in Washington during the War and who was a friend of Colburn and the Lauries, was Simon P. Kase. He wrote The Emancipation Proclamation: How, and by Whom, It Was Given to Abraham Lincoln in 1861, as a confirmation of some of the stories of the Colburns and the Lauries that surfaced in the 1880s.

Simon P. Kase: “one of the most remarkable men of the day” (from Danville Past and Present, 1881)

Map of the Reading & Columbia Rail Road connecting New York via the Jersey Central, Reading and Columbia, with Baltimore and Washington, together with Western R.R. connections to Wheeling and Pittsburg [sic]; compiled by S. P. Kase. (Map at the Library of Congress)

In 1885, as descriptions of the Lincolns’ involvement with spiritualism were beginning to be published, the Lauries’ son, Jack, who was a boy during the Civil War, wrote a letter affirming the Lincolns’ visits to the Lauries’ Georgetown home. Cyrus Poole included it in a larger article he wrote about Abraham Lincoln’s religious convictions.

[…]

My father, the late Cranston Laurie, was a well known and leading Spiritualist for many years prior to his death, all of which time he resided in or near the city of Washington, and was a clerk in the United States post office, holding the especial office of statistician. My mother and sister were mediums. About the commencement of the year 1862, my father became personally acquainted with late President Abraham Lincoln, and my belief is that through my father’s influence, the President became interested in Spiritualism. I have very often seen Mr. Lincoln at my father’s house engaged in attending circles for spiritual phenomena, and generally Mrs. Lincoln was with him. The practice of attending circles by Mr. Lincoln at my father’s house continued from early in 1862, to late in 1863, and during portions of the time such visits were very frequent. This was especially the case after the President’s son Willie died. I remember well one evening when Nettie Colburn, a medium, was present, Mr. Lincoln seemed very deeply interested in the proceedings and asked a great many questions of the spirits.

I have on several occasions seen Mr. Lincoln at a circle at my father’s house, so much influenced, apparently by spiritual forces, that he became partially entranced, and I have heard him make remarks while in that condition, in which he spoke of his deceased son Willie, and said that he saw him. I have on several occasions seen Mr. Lincoln take notes of what was said by mediums. At one circle, I remember that a heavy table was being raised and caused to dance about the room by what purported to be spirits. Mr. Lincoln laughed heartily and said to my father, “Never mind, Cranston, if they break the table, I will give you a new one.” On one occasion, I remember well of hearing my father ask Mr. Lincoln, if he believed the phenomena he had witnessed was caused by spirits, and Mr. Lincoln replied, that he did so believe. This was on a Sunday evening late in 1862. I fix the time by the fact that I was injured the same evening by a runaway horse. In 1862, I was fifteen years of age. My father moved from Washington to a place in the country outside the city late in 1863.

J. C. Laurie.

Sword to and subscribed before me this 1st day of November, 1885.

Theodore Munger,

U.S. Commissioner.

— Cyrus Oliver Poole, “The Religious Convictions of Abraham Lincoln. A Study,” Religio-Philosophical Journal, November 28, 1885.

In reaction to the publication of this letter, Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon, wrote to The Religio-Philosophical Journal.

To the Editor of the Religio-Philosophical Journal:I have carefully read Mr. Poole’s address on Abraham Lincoln, published in the Religio-Philosophical Journal of Nov. 28th, 1885. Mr. Poole is a stranger to me, but I must say that he struck a rich golden vein in Mr. Lincoln’s qualities, characteristics and nature, and has worked it thoroughly and well, exhaustively in his special line.

I know nothing of Lincoln’s belief or disbelief in Spiritualism. I had thought, and now think, that Mr. Lincoln’s original nature was materialistic as opposed to the spiritualistic; was realistic as opposed to idealistic. I cannot say that he believed in Spiritualism, nor can I say that he did not believe in it. He made no revelations to me on this subject, but I have grounds outside, or besides, Mr. Poole’s evidences, of the probability of the fact that he did sometimes attend here, in this city, séances. I am told this by Mr. Ordway, a Spiritualist. I know nothing of this fact on my personal knowledge.

Mr. Lincoln was a kind of fatalist in some aspects of his philosophy, and skeptical in his religion. He was a sad man, a terribly gloomy one—a man of sorrow, if not of agony. This, his state, may have arisen from a defective physical organization, or it may have arisen from some fatalistic idea, that he was to die a sudden and a terrible death. Some unknown power seemed to buzz about his consciousness, his being, his mind, that whispered in his ear. “Look out for danger ahead!” This peculiarity in Mr. Lincoln I had noticed for years, and it is no secret in this city. He has said to me more than once, “Billy, I feel as if I shall meet with some terrible end.” He did not know what would strike him, nor when, nor where, nor how hard; he was a blind intellectual Sampson, struggling and fighting in the dark against the fates. I say on my own personal observation that he felt this for years. Often and often I have resolved to make or get him to reveal the causes of his misery, but I had not the courage nor the impertinence to do it.

When you are in some imminent danger or suppose you are, when you are suffering terribly, do you not call on some power to come to your assistance and give you relief? I do, and all men do. Mr. Lincoln was in great danger, or thought he was, and did as you and I have done: he sincerely invoked and fiercely interrogated all intelligences to give him a true solution of his states—the mysteries and his destiny. He had great—too great confidence in the common judgment of an uneducated people. He believed that the common people had truths that philosophers never dreamed of; and often appealed to that common judgment of the common people over the shoulders of scientists. I am not saying that he did right. I am only stating what I know to be facts, to be truths.

Mr. Lincoln was in some phases of his nature very, very superstitious; and it may be—it is quite probable that he in his gloom, sadness, fear and despair, invoked the spirits of the dead to reveal to him the cause of his states of gloom, sadness, fear and despair. He craved light from all intelligences to flash his way to the unknown future of his life.

May I say to you that I have many, many times, thoroughly sympathized with Mr. Lincoln in his intense sufferings; but I dared not obtrude into the sacred ground of his thoughts that are so sad, so gloomy, and so terrible.

Your Friend,

WM. H. HERNDON.Springfield, Ill., Dec. 4th, 1885.

—William H. Herndon, “Letter from Lincoln’s Old Partner,” Religio-Philosophical Journal, December 12, 1885.

Herndon Reminisces amongst the Lincoln Relics in Chicago

The Poole article—including Jack Laurie’s letter—and Herndon’s letter, stimulated William Henry Chaney, a lawyer who eventually became known for his studies of astrology, to write a remarkable narrative about the Lauries and the Lincolns.

Having read the articles by Messrs. Poole and Herndon, and observing that the latter inclines to the opinion that Mr. Lincoln was a materialist, I think I can make some explanations which will prove of interest to both Spiritualists and Materialists.During the winter of 1865-6 I made the acquaintance of Col. Miller, in New York City. He was the inventor of “Miller’s Steam Condenser,” and made an agreement with me to act as agent for him to introduce it. It will thus be seen that our relations were very intimate. Besides he was one of the most earnest Spiritualists I ever met. He was then between sixty and seventy, but told me that his wife was less than thirty, and lived in Washington. Her maiden name was “Bell” Laurie, and her father had been for thirty years an appointee in the post office. Mr. Laurie, wife and children, were all mediums, and gave frequent séances for members of congress and other distinguished personages at Washington. Isabel, then his [i.e., Miller’s] wife, was the principal medium. In this way Miller first became acquainted with her and wanted her for a wife, because such a wonderful medium. He was negotiating the sale of his condenser at the time, and demanding a million dollars for it. Perhaps this circumstance was not without its weight on the Laurie family, in bringing about this marriage, for I am positive there was never any love between the Colonel and his wife.

From Colonel Miller I first learned about Mr. Lincoln having become a Spiritualist soon after his inauguration. Some senators were telling their experiences one day when the President expressed a curiosity to attend one of the Laurie séances; not that he had the least faith in spirit communion with mortals, but would like to investigate the jugglery practiced. A séance was arranged and he received such wonderful tests that his materialistic ideas were greatly shaken, and after a few more sittings he became a confirmed Spiritualist. But these things were not proclaimed to the public, and this explains why Mr. Herndon was not aware of the change from materialism.

In the spring of 1866, I read in a Washington paper that Judge Carter [i.e., Daniel Kellogg Cartter, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia] had granted a divorce to Isabel Miller from her husband, decreeing to her the guardianship of the children, and also decreeing to her all the rights previously granted to Col. Miller by letters patent for a certain steam condenser. The news was a great shock to me and I hurried to the Colonel for an explanation. Without the least warning, I read the item to him. On looking up I saw he was gasping for breath like a dying man and unable to speak. He had never seen the publication of the summons, nor had he even a hint concerning the matter until I read the item to him. But I soon learned that his distress was all on account of losing the condenser. He said he was very poor—was actually supported by his friends—that Bell never loved him; that she had been having a hard struggle to keep herself and children, and he did not blame her. But the condenser; it had been his pet for eight years; he had been offered half a million for it, and now to lose it—he broke down sobbing. As a lawyer I knew that I could procure a reversal of the decree so far as the condenser was concerned, but I would not tell him so. I was not only his attorney and agent, but his friend, and yet I would not reveal to him what his rights were. Was I not false to my client? Perhaps I was, if judged by the law of the land, but I was true to humanity. I would not have it on my conscience that I had been instrumental in destroying the last hope of that poor young woman and her helpless babes. An orthodox God might have done so and then sent her to sheol for stealing a loaf of bread for her starving children, but orthodoxy is played out with me.

I asked Col. Miller if he would be satisfied if Bell would convey to him one half interest in the condenser. O, yes, he would be perfectly satisfied and he would never trouble her or her children. On this I drew up an agreement, under seal, which he signed and entrusted to me to deliver to her on her signing one transferring one-half of the condenser to him. Thus armed I went to Washington and made the acquaintance of the Laurie family, stopping at the hotel where the old couple were staying. Here Bell came to see me, and I explained matters, saying I would continue to act as agent for both her and the Colonel if she would sign the transfer. She refused until she had consulted some patent right attorneys, and when she learned that I might have got the whole away from her had I been disposed, she ceased to regard me with suspicion, and accepted me as her friend. Her father and mother were also extremely grateful to me. Thus it will be seen how I became very intimate with the Lauries.

I remained in Washington two or three weeks. One day, soon after my arrival, I mentioned the subject of mediumship to Bell. We were in the large hotel parlor, and probably thirty persons, ladies and gentlemen, sitting about in groups. I desired Bell to allow me to accompany her to the piano and witness its tipping to the music, while she played. She objected because a poor performer and because there were some very fine pianists present, but said if I would accompany her to her father’s house, out in the suburbs, that she would then gratify my desire. In turn I objected on the ground that some concealed machinery at her father’s, for tipping the instrument, whereas it was hardly possible at the hotel. After much argument and persuasion she finally consented. I escorted her to the piano and took a seat by her side. She began playing and there was a hush of voices; but it was only for a moment, and I noticed expressions of contempt on the faces of nearly every one present. Bell faltered and would have stopped had not conversation been resumed, and all interest was thus withdrawn from her. Then she began playing a march, and instantly the piano tipped, keeping time with the music. In a moment all gathered about, crowding close to the instrument and vainly trying to discover the cause of the tipping. The diffidence which Bell had shown now all disappeared; her eyes had a far-off look and she appeared like an enthusiast at a sacred shrine. When she had finished the tune I took her seat and tried to raise the piano with my knee, placing my foot on the pedal, as hers was placed, but found that I could not exert a pound pressure unless I withdrew my foot from the pedal. This was one of the best tests of a physical manifestation that I ever witnessed, for the piano weighed nearly half a ton.

During my stay Mrs. Laurie told me many things connected with President Lincoln. Hundreds of times he had consulted Bell, and she preserved scores of his notes, in his own handwriting signed “A. Lincoln,” inviting Bell to come and give him a private séance. It will be remembered that for a long time matters connected with the war went wrong, but when Washington, La Fayette, Jackson, etc., began to be listened to by Lincoln, things went better. Mr. Lincoln consulted these grand old patriots in matters of state as well as war. Sometimes his cabinet would be unanimous in their opposition to some of the President’s measures, but when the spirits assured him he was right he would hold out against the whole world. But all these things were profound State secrets, and even at the time Mrs. Laurie made the revelations to me and showed me the notes in Mr. Lincoln’s well-known chirography, it was under the seal of secresy, and I have faithfully observed it for more than twenty years; but now that so much has been said about it, and there is no longer any reason for silence, I do not feel that I am violating confidence by making this publication.

I have spoken of many matters not strictly pertinent to the main issue, in this case, in order that I might account for my familiarity with the important events, and now for the gratification of the reader, I will add a brief explanation of those facts.

Years before, Col. Miller had put one of his condensers in the Navy Yard at Washington, where it was still at work. Bell and her mother went with me to see it. The engineer assured me that it would condense steam and return it to the boiler at a temperature of 180 [degree mark] Fah. This resulted in a great saving of fuel. About the time the Colonel attached the condenser to a boiler at the Navy Yard a syndicate was formed to buy his patent right. After witnessing its operation they offered him half a million of dollars—counting it down on a table, thinking to tempt him by the sight of the gold, but he stood out for a million. Mr. and Mrs. Laurie and Bell were present, as they all assured me, and coaxed the Colonel to accept it, but he would not yield a particle. Then the capitalists swore that they would sooner spend half a million in preventing him from selling it than give him a penny. The result was that nothing could ever be done with it. The Colonel had many friends besides myself, in both New York and Washington, but our efforts were all in vain. He died in poverty. Mr. Laurie and wife and Bell are all dead and of the children I know nothing.

In conclusion I will relate an incident illustrative of the character of good old Abe, and also showing the esteem in which he held the Laurie family. Mrs. Laurie told it to me with tears in her voice as well as eyes. It was in 1864. Desertions had become so common among the soldiers that it was found necessary to enforce the death penalty most rigorously. A soldier from Maine went home on a furlough. The illness and death of a sister caused him to stay until the thirty days had expired. Then he started, and on landing from the cars in Boston a policeman touched him and asked to see his furlough. Innocently he showed it and was promptly arrested as a deserter. The policeman would get a reward of thirty dollars, and although he soldier assured him he was going back himself, the policeman put him in irons and took him to his regiment near Washington. There was a court martial; the policeman swore the poor fellow’s life away and he was sentenced to be shot at sunrise. A friend to whom the soldier had told everything, mounted a horse after dark, and started for Washington to get a reprieve for thirty days that the soldier might obtain proofs of his statement. It was past midnight when the friend presented himself at the White House. Mr. Lincoln had just retired, leaving strict orders with the sergeant on duty not to allow any one to disturb him, as he had been broken of his rest for several nights. The friend told the sergeant the circumstances, but still he could not admit him. But the sergeant softened enough to tell him that he had orders to admit Mrs. Laurie at any hour, day or night. Then the friend rushed for Mrs. Laurie and told her the strait he was in. Scarcely stopping to dress, she hurried to the White House, reprieve in hand, and was instantly admitted to the room where the President and his wife were asleep. Mr. Lincoln aroused himself with great difficulty. In a few words she explained her mission, which he seemed to understand intuitively more than by his consciousness. Without speaking he motioned her to hand him a pen from the table, and as he put his name to the reprieve, with a moistened eye and trembling lip, he said: “Thank you, Mrs. Laurie; never fear to arouse me on an errand of mercy like this.” The reprieve arrived just in time to prevent a murder. The story of the soldier was corroborated and his life spared. I think President Lincoln was warm hearted enough to be a Spiritualist.

Portland, Oregon.

—Prof. W. H. Chaney, “Was He a Spiritualist? Reminiscences of President Lincoln,” Religio-Philosophical Journal, January 16, 1886.

Elbert F. Turner, aged 21, enlisted as a Private on June 7, 1864 in Washington, DC, in Company U, 3rd Infantry RA. He was discharged on December 22, 1864, three days after Mrs. Laurie wrote her letter.

Chaney’s description of Belle Laurie Miller’s stealthy legal action against her husband, including her effort to acquire his patent, does not necessarily inspire confidence in her. Apparently she made more than one effort to insure her success: A bill was introduced into the Senate Patent Committee to force the transfer of the patent in full. It was passed in April 1869.

In 1866, Belle had remarried. She was Belle (or Isabella) C. Youngs, wife of Theophilus Youngs.

Bills of the 40th Congress, 3rd Session and Private Acts of 41st Congress, 1st Session “Patent of James M. Miller renewed to Isabella C. Youngs” (April 1, 1869). (Congressional Legislation at the Library of Congress: search under “Isabella C. Youngs”).

Affidavit of Isabella C. Youngs

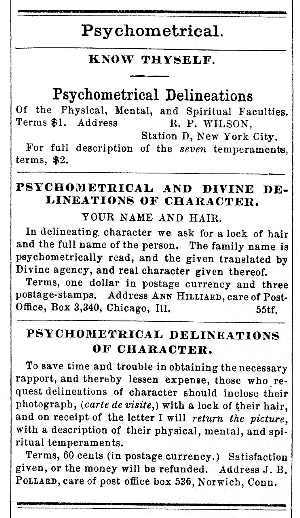

It was as “Belle C. Youngs” that her name appears on the April 1866 note accompanying the lock of Lincoln’s hair at the Chicago Historical Society, along with her mother’s name, “Mrs. M. Laurie.”

Belle Youngs and a Question of Identity

Before considering the provenance of the lock of hair, a brief look at Belle Youngs’ later life is in order. According to her, she served as a battlefield and hospital nurse during the Civil War, sustaining several bullet wounds. Again on her account, President Lincoln gave her a gold medal “for devotion to sick and wounded soldiers during the war.” While visiting the sick in prison in 1861, she met a soldier imprisoned for desertion. It was Theophilus Youngs, a mechanic from New York City who said he had “lost his certificate of discharge.” After Belle married him in 1866, Theophilus was given an appointment as a clerk in the Quartermaster General’s Department through the influence of his father-in-law, but stayed there only a few years, and left that position when his profligate ways sent the family into debt. He and Belle and their children moved to Boston, where he worked as a mechanic, and she found clients for her abilities as a medium, including her abilities as a “medical medium and electro-magnetic healer.”

In 1873, Theophilus Youngs went missing. Two years later, a body that had been washed up on shore near Boston was identified by a workman who knew the Youngs family, as being that of Mr. Youngs. Belle Youngs, who now went by her first name and called herself Mary I. C. Youngs, buried her husband and set about to reclaim an inheritance from his father that his brother Henry Youngs claimed based on a promissory note from Theophilus and Belle that had transferred their portion of the inheritance to Henry in exchange for an unredeemed loan.

When the case finally went to a New York court in 1880, Theophilus’ brother contested it as the hearing opened—on the basis that Belle was not really the administrator of Theophilus’ estate because Theophilus was not really dead. The next day, Henry’s lawyer triumphantly produced a man he introduced to the Court as Theophilus, found and returned. Belle, however, turned the Court—and the New York newspaper reporters—on its head, by looking the man in the eyes and declaring that he was not her husband Theophilus. She asked the Court to have him arrested.

Over the next several months, The New York Times covered this strange and sensational case in detail, as it unfolded in court. Witnesses were brought in on both sides, testifying for or against a positive identification of the man in question as Theophilus Youngs.

Reporters came to believe that Theophilus had simply dropped out of sight in an effort to escape the rather “prepossessing” Belle. He had left his wife and children and made his way out West, to Colorado and the Black Hills. The reporting suggested that his brother Henry actually knew the situation, but kept it secret, and only brought his brother back to New York City when he needed him to protect Henry’s interests. Henry Youngs denied this. The reporting further suggested that Belle, discovering that her claim to her husband’s possible inheritance would be strengthened only if she were Theophilus’ certain widow rather than his uncertain one, had been able to convince the workman to identify a body that had washed ashore as being her husband’s.

Hearings on this case dragged on from October through the following May. Theophilus, as revealed through the newspaper’s reporting on the Court’s questioning of him, was a phlegmatic and unskillful grifter and alcoholic, who had been arrested before on bigamy charges, but who, nevertheless, was indeed Belle Youngs’ husband, no matter how much she denied it. Among the small bits of information that Theophilus offered in Court about his wife and family, as evidence of his knowledge of them, was a comment on the medal that Belle wore around her neck, given to her by Lincoln. “The alleged Theophilus,” reported The Times, “says he never heard of this medal while he lived with his wife, and doesn’t believe Lincoln gave it to her.”

The hearings dissipated eventually, rather than ending abruptly. However, an end was reached when Belle died of a heart attack, at her home in Oxen Run, just outside of Washington, on April 11, 1882. Several months later, Theophilus made the newspapers again by being arrested in Boston for stealing twenty-five dollars from a lady friend.

The Lincoln Lock of Hair in Chicago

The association of the Chicago Historical Society’s lock of hair with the names of Margaret Laurie and Bell Laurie Youngs presents an interesting, but complex background for weighing the likelihood of its authenticity.  The Lauries’ biographies certainly raise the issue of veracity—making pianos float in the air, delivering messages to the Lincolns and to others from disembodied spirits, Belle’s surpassingly odd encounter with the question of the identity of her husband, and Theophilus’ statement about the authenticity of her Lincoln medal are all things that do not fill one with confidence about any claims the Lauries may have made about the authenticity of a relic—especially if such claims made a difference in whether an item was worth something on the collectors’ market.

The Lauries’ biographies certainly raise the issue of veracity—making pianos float in the air, delivering messages to the Lincolns and to others from disembodied spirits, Belle’s surpassingly odd encounter with the question of the identity of her husband, and Theophilus’ statement about the authenticity of her Lincoln medal are all things that do not fill one with confidence about any claims the Lauries may have made about the authenticity of a relic—especially if such claims made a difference in whether an item was worth something on the collectors’ market.

On the other hand, almost no one was in a better position to obtain a lock of Lincoln’s hair after his death. Nor was anyone else better able to make a claim—at least to Mary Todd Lincoln—for the need to have physical possession of a lock of her husband’s hair. With that lock of hair, the Lauries would have told her, they would be able to maintain for Mrs. Lincoln a psychometric connection with her husband. If the hair lock were cut from the spot next to where the bullet passed through the President’s head, that was better for making spirit contact, because the lock of hair would carry the mental energy from where his life’s blood had departed his body. The use of locks of hair for psychometric examination, diagnosis, and healing, and for making psychic contact with the owner of the hair, was a well-established practice among mediums of the time. The power attributed to the lock of hair, when used by mediums, was far more than that attributed to locks of hair in common funerary practices—where commemorative hair relics were saved and treasured, and woven and braided into mementos.

No matter what one may think of Margaret and Belle Laurie, Mrs. Lincoln appears to have thought highly of them. During the autopsy of the President, Mary Todd Lincoln sent word in to the surgeons, requesting a lock of hair be cut and sent to her. This was done. A few other locks of hair were then cut as well for the attending physicians. What happened to Mary’s lock? We may imagine that she gave it—or a portion of it—to her confidantes, the Lauries, whom she believed could keep her in contact with her husband. One of the Lincolns’ bodyguards who had taken up his responsibilities not long before the assassination, later wrote:

The days during which the President lay in state before they took him away for his long progress over the country he had saved were even more distressing than grief would have made them. Mrs. Lincoln was almost frantic with suffering. Women spiritualists in some way gained access to her. They poured into her ears pretended messages from her dead husband. Mrs. Lincoln was so weakened that she had not force enough to resist the cruel cheat. These women nearly crazed her. Mr. Robert Lincoln, who had to take his place now at the head of the family, finally ordered them out of the house.—Crook, William Henry. Through Five Administrations; Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, Body-Guard to President Lincoln. New York: Harper Brothers, 1910: 69-70.

In fact, Mary’s son Robert shortly used his mother’s recourse to spirit mediums as part of his reasons for testifying that she should be committed to a mental institution.

Ironically, all this makes it more likely that in fact the Lauries did possess a lock of Lincoln’s hair, and consequently makes it more likely that the Chicago Historical Society’s relic—having naively preserved, all through the years, its association with the Lauries—is genuine, and that it may have been part or all of the lock of hair that Mary Todd Lincoln requested during the autopsy.

[Cranstoun Laurie, his wife Margaret, and their son Jack C. Laurie, are all buried in a plot that bears no markers today in the Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Bell Youngs is also interred in the Cemetery, in a different unmarked plot, as are her grandparents, Rev. James Laurie and Elizabeth Laurie.]

More References

Miller, James M. Remarks on Marine Life-Saving Inventions, in Connection with the Report Made to Congress, March 2, 1868. New York, 1868.

“Mrs. Mary I. C. Young[s]. Her Examination before the New York Protective Committee.” The Religio-Philosophical Journal (Chicago), August 14, 1875.

“Mr. Youngs or Not Mr. Youngs. His Brother Says It Is Mr. Youngs, His Wife Says It Is Not.” The New York Times, October 21, 1880.

“Mr. Theophilus Youngs’s Case. Near Relatives Swear the Man in Court Is Surely He—The Other Side.” The New York Times, October 22, 1880.

“A Mystery To Be Solved. Is Theophilus Youngs Dead or Alive? The Strange Case Which Puzzles the Surrogate—An Alleged Theophilus Turns Up and Is Recognized by His Brother and Others, but Repudiated by His Wife.” The New York Times, November 30, 1880.

“Youngs and His Daughter. Scars on Their Fingers Lead to Identification. Probable Ending of a Very Curious Case—An Interesting Interview—Mrs. Youngs’s Lawyer Nearly Satisfied—The Wanderings of Theophilus—Litigation Previous to the Present.” The New York Times, December 1, 1880.

“Theophilus Youngs’s Story. He Says He Is the Husband of a Woman Who Says She Is a Widow.” The New York Times, January 30, 1881.

“Sale of ‘Eckington’ Ordered. A Historical Estate.” The Washington Evening Star, February 5, 1881.

“Theophilus Youngs in Court. He Refuses to Give Any Account of His Wanderings.” The New York Times, February 12, 1881.

“Identifying Theophilus Youngs.” The New York Times, February 19, 1881.

“The Alleged Theophilus. Mrs. Youngs Repudiates Him after an Examination.” The New York Times, March 2, 1881.

“Theophilus Youngs Again. If This Man Be He His Own Child Denies Him. Alice Youngs Declares That He Is Not Her Father—Why She Recently Wept As If He Were—Men Who Say He Is the True Theophilus.” The New York Times, March 17, 1881.

“Not the True Theophilus.” The New York Times, April 19, 1881.

“The Theophilus Youngs Case.” The New York Times, May 3, 1881.

“City and Suburban News.” The New York Times, May 11, 1881.

“The Disputed Theophilus.” The New York Times, May 18, 1881.

“Theophilus Youngs’s Bald Spot.” The New York Times, May 24, 1881.

“City and Suburban News.” The New York Times, May 27, 1881.

“Mrs. Theophilus Youngs Dead.” The New York Times, March 14, 1882.

“Not Solved by Mrs. Youngs’s Death.” The New York Tribune, March 19, 1882.

“Theophilus Youngs Again. He Is Accused of Stealing $25 in Boston and Found Guilty.” The New York Times, August 12, 1882.

Thanks for help from:

Jerry A. McCoy, at the Peabody Room of the Georgetown Branch Library of the District of Columbia Public Library.

James Adams, at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, Washington, D. C.

Bill Davis, at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D. C.

Sandy Schmidt, at the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D. C.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ Ephemera Home ] [ Civil War ]